Actually, left turns are one of the most tricky situations to handle for novice or experienced cyclists alike. They can be a source of confusion and stress, and even trigger conflicts between drivers and cyclists.

For this reason, it is important to carefully plan one's route to minimize the occurence of difficult left turns. When they cannot be avoided, one should ideally decide ahead of time what strategy will be used at a given intersection. In my experience, leaving that decision to the last minute can lead to impulsive and unsafe riding.

In most of the world, traffic keeps to the right side of the road. This being said, a around a third of the world population lives under left-hand traffic (LHT) rules.

Britain aside, many of the places that still have LHT are former British colonies, such as India, though there are others left-hand driving countries without a history of British colonialism like Japan and Indonesia.

As you might have guessed, this page is written under the assumption of right-hand traffic, though the concepts are analoguous for right turns in left-hand traffic zones.

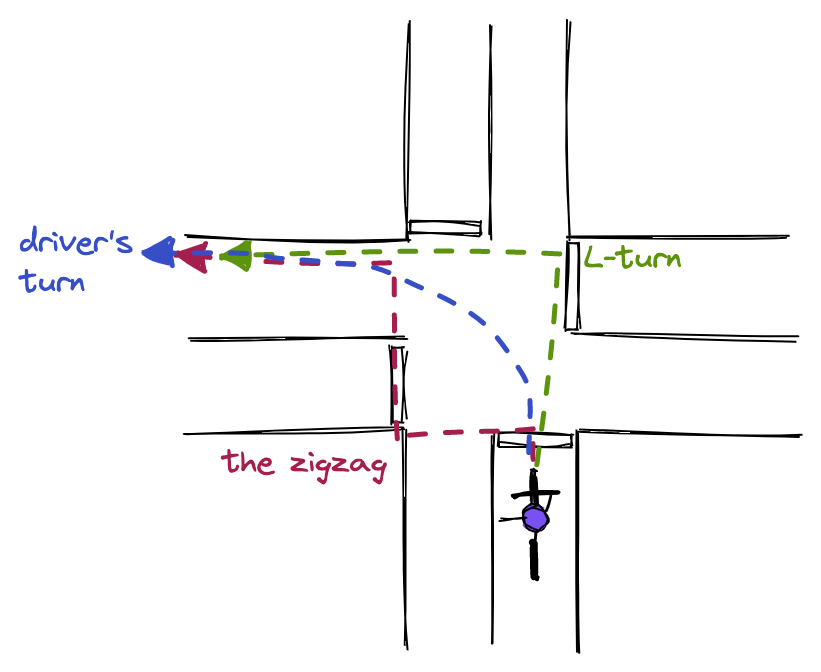

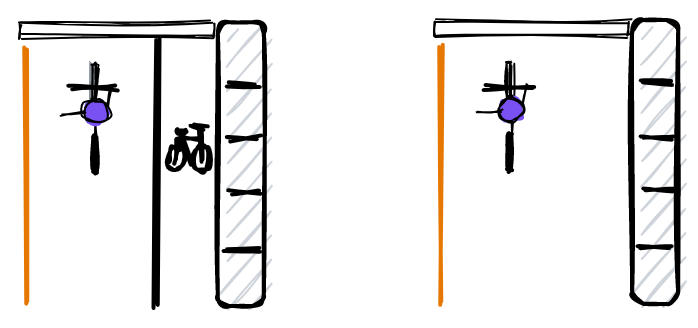

The following picture illustrates three common ways in which a cyclist can handle a left turn.

For the sake of this post, let's call them as follows (ordered in terms of preference):

As the name hints, this type of turn simply consists in turning mostly like a car would. Although it sounds simple, many novice cyclists are intimidated by this maneuver because it involves taking space in the left lane, amongst traffic and far from the curb.

It is ok not to feel comfortable turning this way and many cyclists who have ridden for a long time are still avoiding it. However, it can save time for those cyclists who feel at ease taking their share of the road.

This turn is my personal favorite when it can be executed safely. In general, it is the fastest turn of the three as it requires at most a single traffic light cycle.

Occasionally, a driver might take place on your right and turn left at the same time as you. This situation can happen if you are positioned too much towards the left-hand side or not clearly signalling your intention to turn left. Even if you did everything right, you may also simply be pushed around by an abusive driver who does not like waiting behind a cyclist.

This happened to me once. After the turn, I was not able to move back towards the right-hand side of the street because a car would be on my right and was obviously not in a mood to yield to a cyclist. The driver probably thought it was fun to watch a poor cyclist stuck in the middle of a busy road making gestures of despair and stuck out her best finger. There is unfortunately not much to be done with such lunacy, and I accelerated to overtake the next car stuck in traffic.

Presumably, if the person behind the wheel seems like a decent human being and the error was done in good faith, it might be best to keep calm, signal right and hope that the driver will let you get through. Prevention is always a good idea - by staying in the center of the left lane, it becomes harder for a car to pretend you are not there.

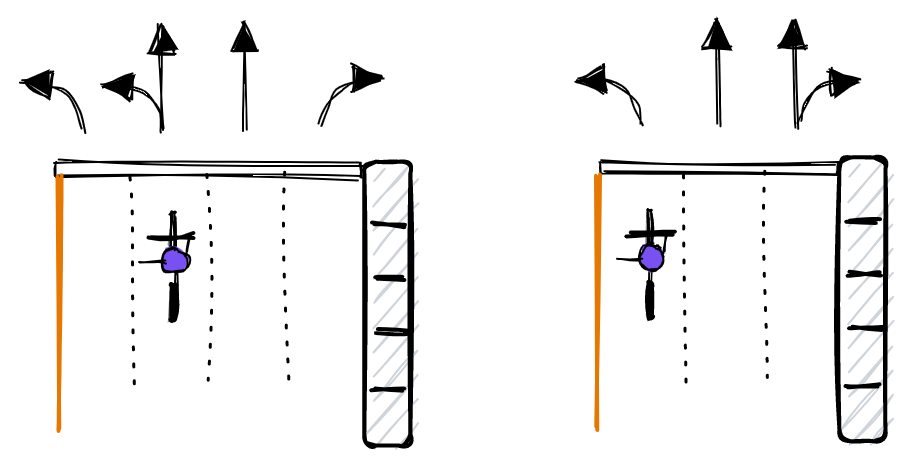

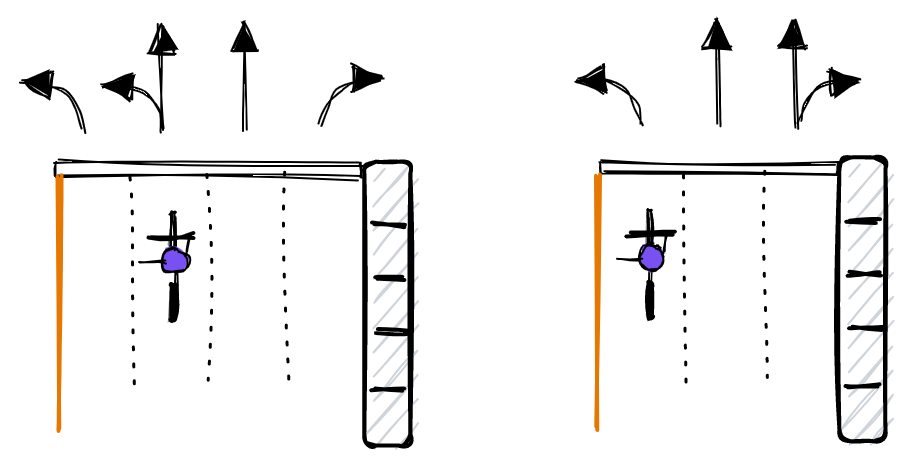

This is the trickest part and is a skill that is improved with practice. The cyclist has to be positioned left by the time he reaches the stop line of the intersection.

I sometimes see novice cyclists suddently turning left from the right-hand side of the road once they reach the stop line. This is quite dangerous as the cyclist might cut off incoming traffic and surprise drivers. Because the cyclist has to look out both for traffic coming from behind and in the opposite direction, it is easy to make a mistake and fail to see a driver coming by.

The better option is to make a move towards the left of the road ahead of the intersection, but it is not always easy. The ideal situation is when there is a gap in traffic around 10 seconds before arriving at the intersection, which makes it easy to move towards the left just in time and avoids staying there for an incomfortably long stretch of road.

In theory the cyclist can move towards the left whenever the road is free behind him, which means that on busier roads he would be right to take his space on the left lane whenever conditions are safe to do so.

In practice, this can be intimidating and I wouldn't recommend it for busier streets with high-speed traffic. I have been honked and overtaken by the right a few times trying this approach on main arteries and it's an unnecessary stress that I don't need in my day. Some cyclists are able to keep their cool and might be able to calmly explain to toxic drivers why it is their right to be there. If this is you, please keep it up! In other cases, the L-turn might be a wiser choice. With time, you will get a feel for the situations in which you are comfortable with performing this maneuver.

This is the basic maneuver that most cyclists would instinctively perform when they need to make a left turn.

With L-turns, the intersection is crossed in two steps and the cyclist always stays on the right-hand side of road. It is a perfectly fine turn, though maybe "boring", and well-suited to busy or large intersections.

In some cases, one might have been preparing for an L-turn but decides to change to a botched driver's turn at the last minute. This is tempting as it allows completing the maneuver in one single cycle. In my opinion, this is not a safe behavior and should be avoided, but hey, we're all humans.

I find that it helps to plan the left-turn strategy ahead of time to prevent this impulsive move. If this happens a lot at a specific intersection on your commute, it might be a sign that it would be better handled through a driver's turn.

As a general rule, one should avoid blocking any type of traffic while waiting at the far corner (pedestrian, cycling or driving). If there are cycling or pedestrian lanes near where you are waiting, or if the car traffic comes close to the sidewalk, you want to make sure you are out of the way. This is usually the main reason why I would wait on the sidewalk as opposed to on the street.

This danger can be easy to overlook. When doing an L-turn and crossing from corner to corner, the cyclist is separated from the car traffic. After the second crossing, the cyclist has to quickly merge back onto the street to take his place in the curb and avoid obstacles such as parked cars.

When performed in a sudden manner, this move can surprise drivers, so it is important to signal your intention of merging back in the traffic, especially if the road is busy behind you.

This issue is less of a problem if you positioned yourself to be in the curb with the traffic on the perpendicular street while waiting for the second crossing. In some situations, it makes sense to reposition oneself at the corner bewteen the 1st and 2nd crossings to be ready to hit the road when the light turns green.

What I call the "zigzag" move consists in crossing the current street first, then the perpendicular street. In some ways it is a mirror image of the L-turn, but because there are three 90° turns, it looks more like an ugly "Z" than a nice "L". As you might have guessed from the name, I find this maneuver tricky and dangerous and would not recommend it, unless done completely as a pedestrian.

The main reason I am against this move is that it puts the cyclist on the left side of the street while crossing which is not natural. Turning cars tend to not to be watchful for cyclists circulating on the left-hand side.

To make things worse, a cyclist will be tempted to cross the first street from a high-speed riding position in the lane, suddenly making a sharp left turn towards an unnatural direction. In my opinion, moving with the flow of the traffic is a common-sense strategy which is preferable to this type of maneuver. I will not further discuss it here, but would love your feedback on this part, especially if you find this move useful for you!

In Canada, multi-lane intersections are often marked with arrows to indicate the allowed directions of traffic for each lane. When turning left, one should follow the rightmost lane where left turns are allowed. The reason is simple: after the turn, it has to be easy to move back to the curb. As discussed earlier, I would avoid getting too close to the left of the lane to make sure that cars wait behind. I find that staying in the center of the turning lane is usually a good rule of thumb.

If the lane turning left also allows going straight, the cyclist might move a bit more towards the left as an to make it easier for drivers going straight to get around him.

For single lane streets, the cyclist should move towards the left of the lane before the turn. This fact is independent of whether there is a cycling lane on the street. Turning left from a cycling lane on the right-hand side of the street is against the Rule of Expected Behavior.

Unfortunately, bike "infrastructure" (if that's what we can call a painted line on the ground) is not always well thought-out and can encourage unsafe behavior. Note however that such cycling lanes could be used to make an L-turn instead.

Figuring out the best way to get somewhere on two wheels is one of the most important aspects of urban cycling. There are many factors to consider, but avoiding left turns at busy intersections is near the top of the list.

What matters the most is the traffic on the street on which the cyclist is preparing the turn. Turning from a side street to a major artery (given there is a traffic light) is usually not a big deal, but the other way around can be more intimidating.

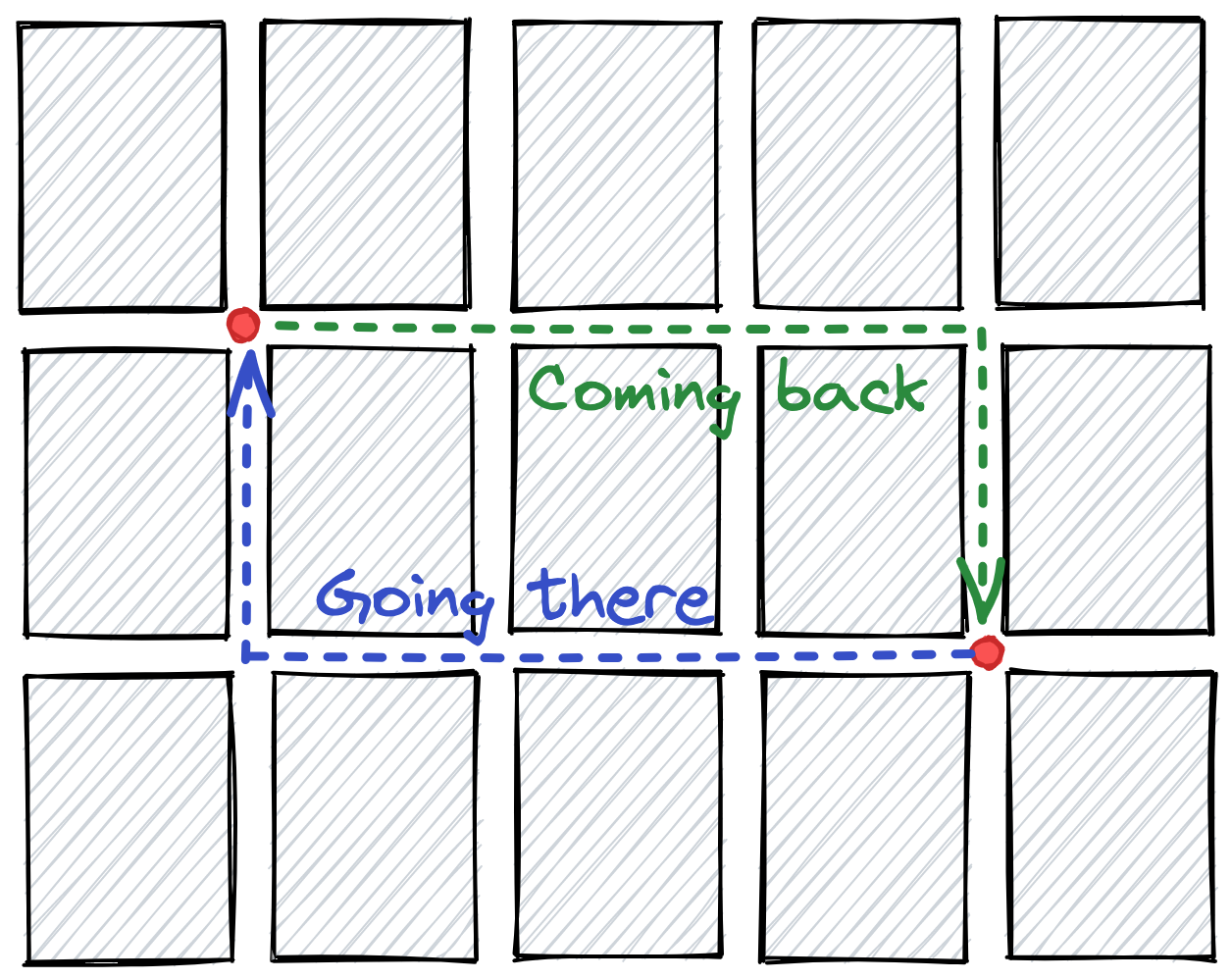

Sometimes, avoiding left turns might mean that the morning and evening commutes take diffent routes. The simplistic example below shows how travelling between two locations is possible by always turning right in either direction. Of course, real-life situations are not often as simple as this one but you get the idea. By carefully studying the street grid along one's commute, it is sometimes possible to optimize it to minimize the amount of left turns, or at least make it such that they occur at intersections that are not so wide or busy.